The fast 35mm prime is a staple of the photographic industry.

And with good reason.

For starters, it’s one of the most versatile lenses money can buy; it’s great for reportage, street photography, environmental portraiture, landscape photography… you name it.

It should come as no surprise that every serious camera system offers at least one of these lenses. They’re usually big, heavy, and expensive, sometimes even ridiculously so. On the other hand, they tend to deliver some of the finest image quality available. I know, life’s full of hard choices.

The Sony Zeiss Distagon T* FE 35mm f1.4 ZA lens is all of those things, and then some. It’s one of the biggest prime lenses in the E-mount system, and also one of the most expensive. Luckily, it also happens to pack quite a punch in the image quality department.

Let’s take a closer look at it.

The Sony Zeiss Distagon T* FE 35mm f1.4 ZA is a fast wide-angle prime, one of the most versatile lenses money can buy.

Build quality and ergonomics

Like every lens jointly released by Sony and Zeiss so far, this 35mm f/1.4 lens is very well built. Being a Sony Zeiss collaboration, the lens was designed by the two companies and then manufactured by Sony according to Carl Zeiss specifications. Lenses produced in this manner are then quality-checked by Zeiss to ensure certain design and performance parameters are met.

Sony makes this lens in Thailand, according to Carl Zeiss specifications.

The lens shares many of its build and design features with other high-end Sony Zeiss lenses, like the excellent 50mm f/1.4 prime lens.

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens shares many design features with other FE lenses, like the excellent 50mm f/1.4.

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens sports an all-metal exterior, except for both lens caps and the lens hood, which are made of plastic. It is also weather-sealed and rated by Sony as “dust and moisture resistant”, just like the α7-series cameras. What this means in practice is that, while you probably shouldn’t take it out under torrential rain, or dip it in water — definitely don’t dip in water — it should be just fine to use under a light drizzle.

Cosmetically, the design of the lens is very clean, with lots of straight lines and very little in the way of embellishments — much like the other Sony FE lenses. The lens sports the famous blue Zeiss badge on one side of the barrel, and the Sony logo on the opposite side.

There’s a dedicated aperture ring on the lens, a high-end feature that is currently only found in the very best prime lenses in the FE system: the Sony Zeiss Planar T* 50mm F1.4 ZA, the Sony FE 85mm F1.4 G-Master, the new Sony FE 100mm F2.8 STF G-Master, and this lens.

The aperture ring has a nice feeling to it and has markings every 1/3rd of a stop. Additionally, it can be de-clicked for smooth aperture switching during video recording by toggling a switch on the lower part of the lens barrel. This is a very nice feature, but unfortunately in my copy of the lens, the switch is a bit loose, which makes it extremely easy to toggle by accident. On several occasions I’ve accidentally de-clicked the aperture ring during a shoot — while it’s admittedly not a big deal, those brief interruptions did make me lose my focus.

The lens has an aperture ring with markings every 1/3rd of a stop. The ring can also be de-clicked for smooth aperture switching during video recording.

Unfortunately in my copy of the lens the switch is a bit loose, making it very easy to toggle by mistake.

A good portion of the lens barrel is devoted to the focusing ring, which makes using the lens easier and more comfortable. This ring is made of metal and has a nice textured surface that improves the grip.

Resistance to the focusing ring is just about perfect — not too stiff and not too soft. This is an improvement over some other FE lenses that feature very soft focusing rings, although it may simply be a matter of varying manufacturing tolerances. I’d need to sample a few more units of the lens to draw a definitive conclusion.

The focusing ring is made of metal and has a textured surface to improve the grip.

The included lens hood is made of plastic, but it feels nice and solid and can be reversed for easy storage. It locks into place with a reassuring click and it doesn’t take a huge amount of effort unlock. Again, there’s probably some variation depending on manufacturing tolerances, so your experience may differ somewhat from mine.

The included lens hood is made of plastic, but it’s very solid. It locks into place with a reassuring click.

The filter thread size is 72mm, which is currently one of the biggest sizes in use in the FE system, second only to the 77mm of some of the most recent G-Master lenses announced by Sony. Other FE lenses that use this same filter size include the Sony Zeiss FE 16-35mm f/4, the Sony Zeiss FE 50mm f/1.4 Planar, and the Sony 70-200mm f/4 G OSS zoom lens.

The filter thread has a diameter of 72mm, which is also used by some of the most popular lenses in the system.

Overall, the build quality of this 35mm f/1.4 lens is top-notch, with very little to complain about. Manufacturing tolerances aside, it’s a solid piece of glass that will surely hold up for many years of professional use. Weight-wise, it comes in at 1.39 lbs (630 g), which is rather on the heavy side for a prime lens, but reasonable considering its size and f/1.4 aperture.

Overall, the lens feels very solid in the hand and its build quality is top-notch.

Manual focus

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens uses a focus-by-wire mechanism. This means the focusing ring is not mechanically linked to the focusing system, which is instead operated electronically. Manual focus users tend to prefer lenses with actual, mechanically coupled manual focus implementations, like the Zeiss Loxia line, but this lens still manages to offer a pretty good manual focus experience thanks to many focusing aids built into modern Sony cameras.

The MF aids built into modern Sony cameras make manual focusing a breeze with this lens.

When used in combination with features like focus peaking and magnification, it’s pretty easy to nail focus every time with this lens, and with some practice it’s entirely possible to obtain results that are even competitive with the AF system. This is especially true in low light scenarios, where any lens will tend to hunt for focus a little bit.

Most modern E-mount Sony cameras can be configured in DMF mode, meaning you can use the AF system to achieve general focus, then turn the focusing ring to achieve critical focus manually. In this mode, focus peaking is activated by default, but you can set the camera to use magnification instead. This is a fantastic way to ensure you always focus exactly where you want to. Having said that, keep in mind that at f/1.4 depth of field will be so shallow that even the slightest movement may cause you to lose focus. In order to focus manually with this lens wide open, proper camera technique is absolutely required.

Manual focus works great in low light, where the AF system may hunt, or as an aid to fine-tune for critical focus.

Finally, the lack of a depth-of-field scale and hard stops is unfortunate. You will need to keep an eye on the EVF or the LCD screen, which means this lens probably won’t cut it for those who like to use the zone focusing technique. For everyone else, though, the experience is pretty solid.

No hard stops or depth of field scale leave some room for improvement, but the lens still offers a pretty solid MF implementation.

Autofocus

Autofocus performance is great in good light, as is typical with most FE lenses. Please note that AF performance is also dependent on the camera body, so your mileage may vary. This review was written based on the experience of using this lens on the Sony α7 II.

In good light, the Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens achieves focus pretty quickly in any sort of scene, provided there are at least a few contrasty lines to help the AF system figure out where to focus. Considering the amount of glass inside this lens, one shouldn’t expect it to be an instant-AF lens. It’s fast, but not that fast, like most wide aperture primes these days.

AF performance is great in good lighting conditions, about as fast as one could expect from an f/1.4 lens like this one.

In dimmer conditions, AF performance slows down significantly, as with pretty much all lenses. It remains usable for the most part, but if you’re stopping the lens down a lot, you may be better served by using manual focus instead.

Focus accuracy is excellent, which is impressive for a lens this fast. Depth of field is super shallow at f/1.4, so it’s nice to see that accuracy wasn’t compromised for the sake of speed.

The minimum focus distance is rated at 30 cm, which is pretty good for a fast prime like this. That distance is measured from the camera sensor to the subject, so the front element of the lens can get quite close to the subject and the lens will still focus correctly. While this is not a Macro lens, it’s nice to have this close-focusing ability out of the box.

The Sony Zeiss f/1.4 is by no means a sports-oriented lens, but by setting the camera to AF-C mode and with subject tracking turned on, it is able to accurately track moving subjects in most situations when used on a Sony α7 II camera. Tracking performance may vary slightly when used on different camera bodies, but it should remain good enough to track everyday subjects, like people walking or riding a bicycle. Obviously, stopping the lens down helps significantly here due to the increased depth of field, but the lens does an acceptable job even when shooting wide open at f/1.4.

By setting the camera to AF-C mode with subject tracking turned on, the lens is able to track everyday subjects reasonably well.

The 35mm f/1.4 lens is virtually silent while focusing, which makes it well suited for all purposes, including video recording. Unfortunately, the lens breathes significantly, which may put some people off for video use. If video is your primary goal, you may want to consider this before buying.

Image quality

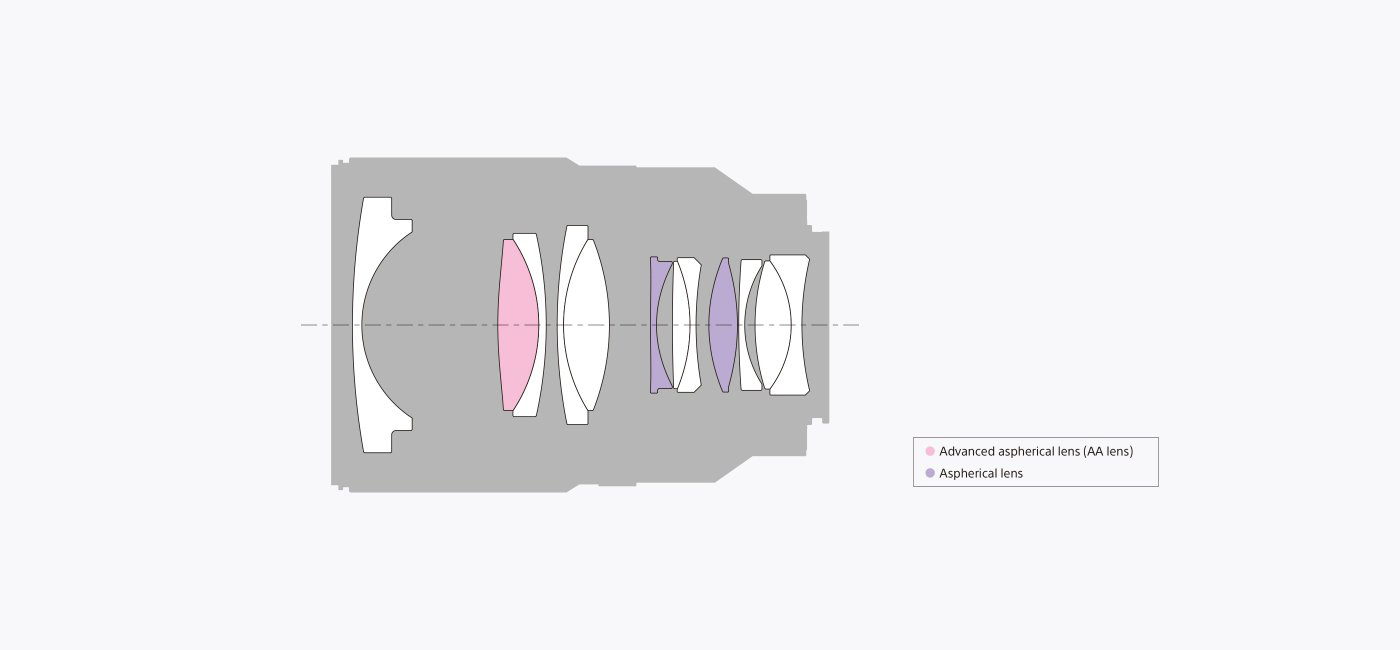

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens uses Zeiss’ Distagon optical formula. This is a type of retrofocus design — also called inverted telelens — pioneered by Carl Zeiss in the 1950s. Distagon designs make it possible to produce wide angle lenses while still maintaining a large distance between the rear element and the image plane, which helps correct distortion.

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens uses a Distagon formula, which is a type of retrofocus design that makes it possible to create wide angle lenses without distortion. Image: Sony.

This Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens has 12 elements in 8 groups, including 2 aspherical elements and 1 advanced aspherical element, all of which which supposedly help correct aberrations. Now, this lens is a modern entrant in a pretty crowded and popular lens category, so it has some pretty big shoes to fill. The bar is already set high by the likes of Leica, Canon, Sigma, and Zeiss themselves, too, so let’s see how this one performs.

Sharpness

Sharpness is excellent across the frame with the Sony Zeiss FE 35mm f/1.4 lens, even wide open. This is one of the sharpest 35mm lenses available for any camera system, and it performs roughly in line with the rest of the high-end FE primes.

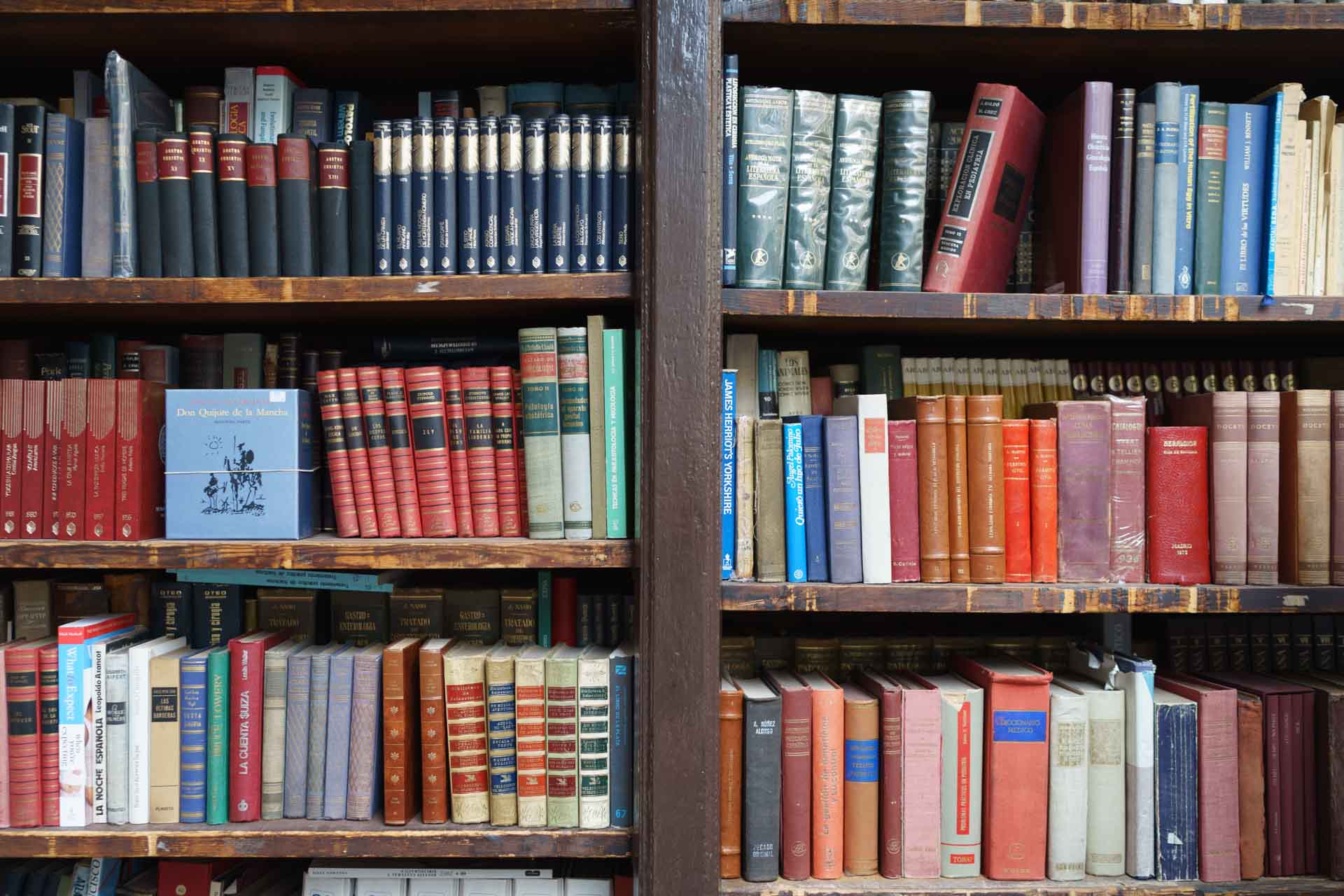

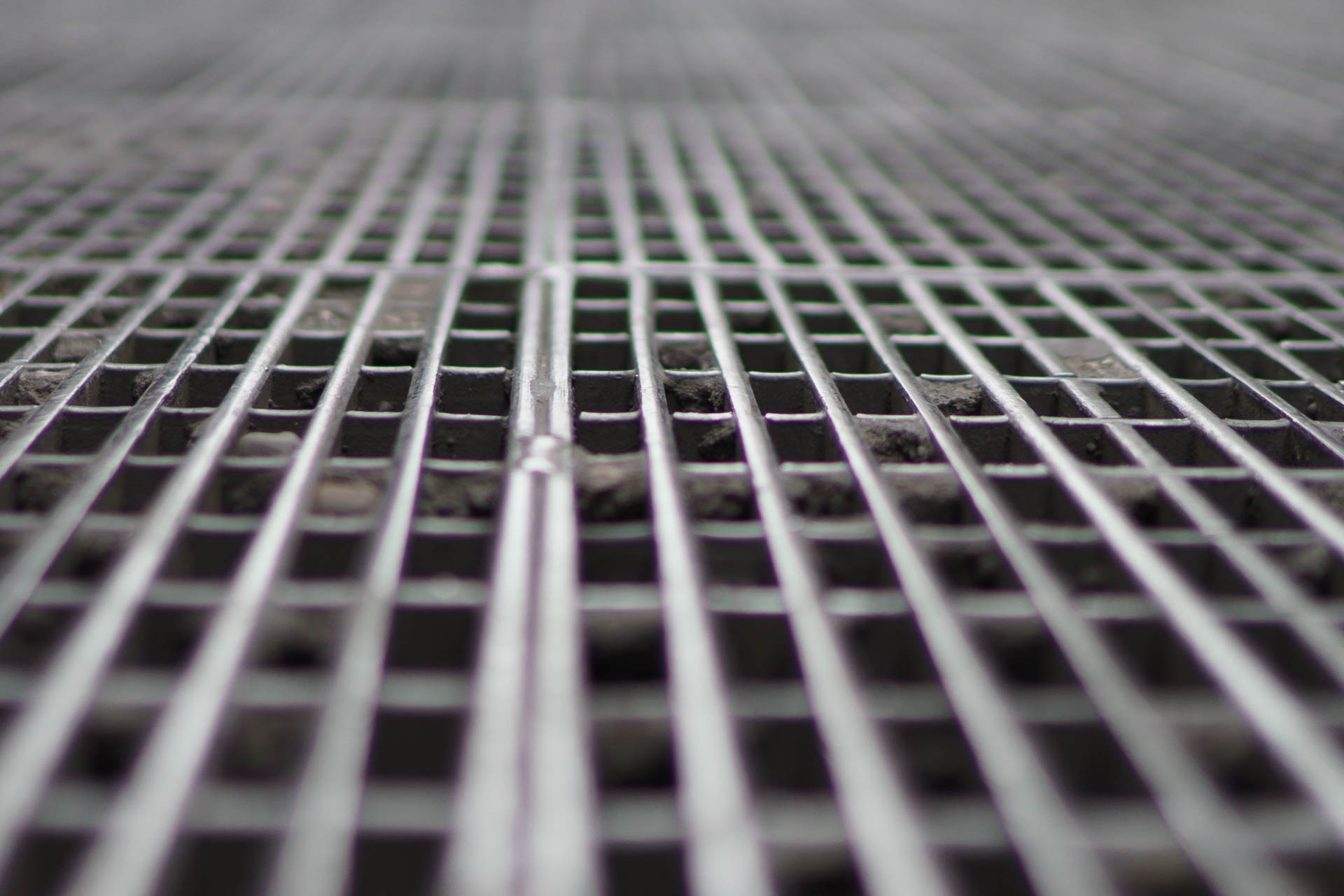

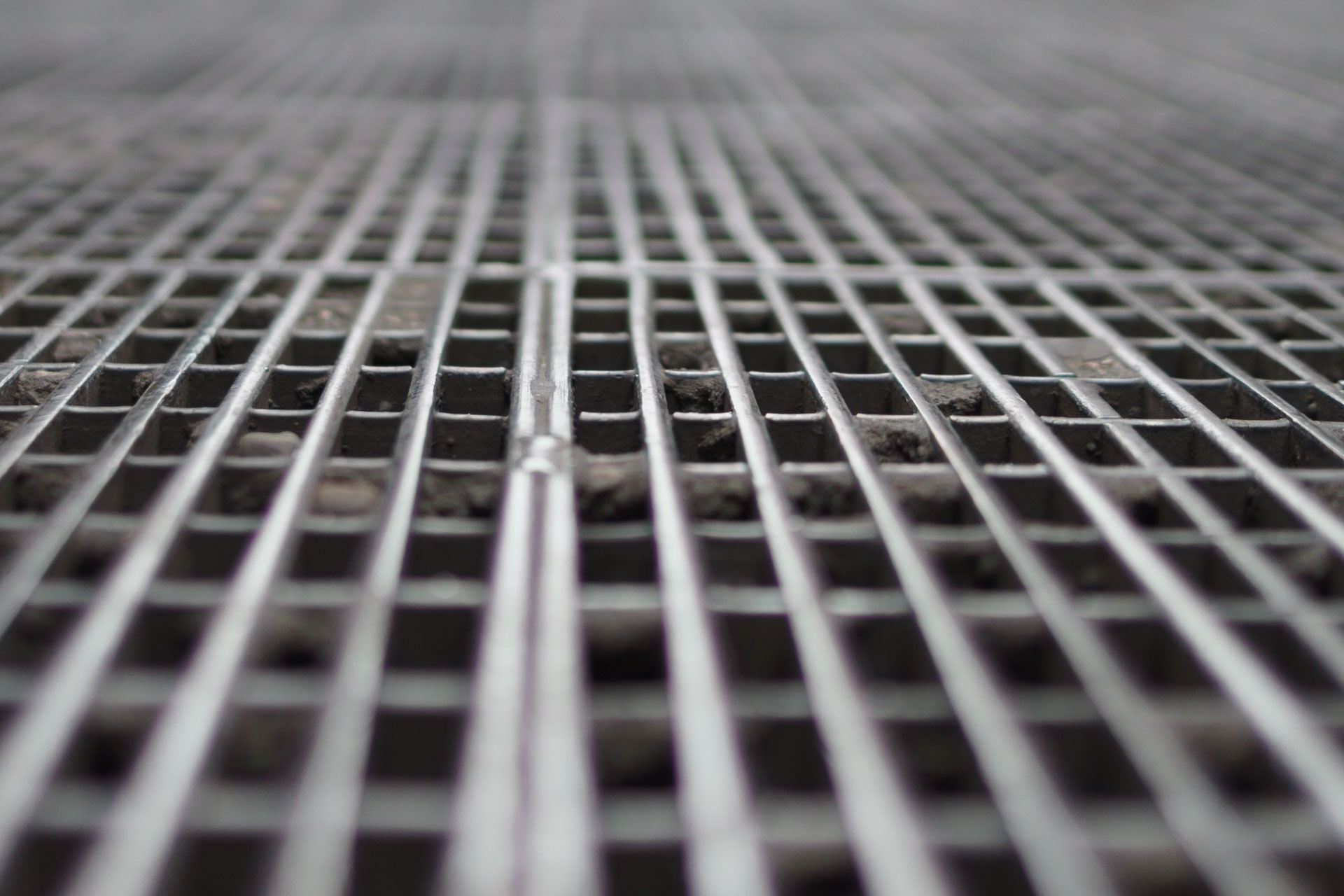

Sharpness test scene.

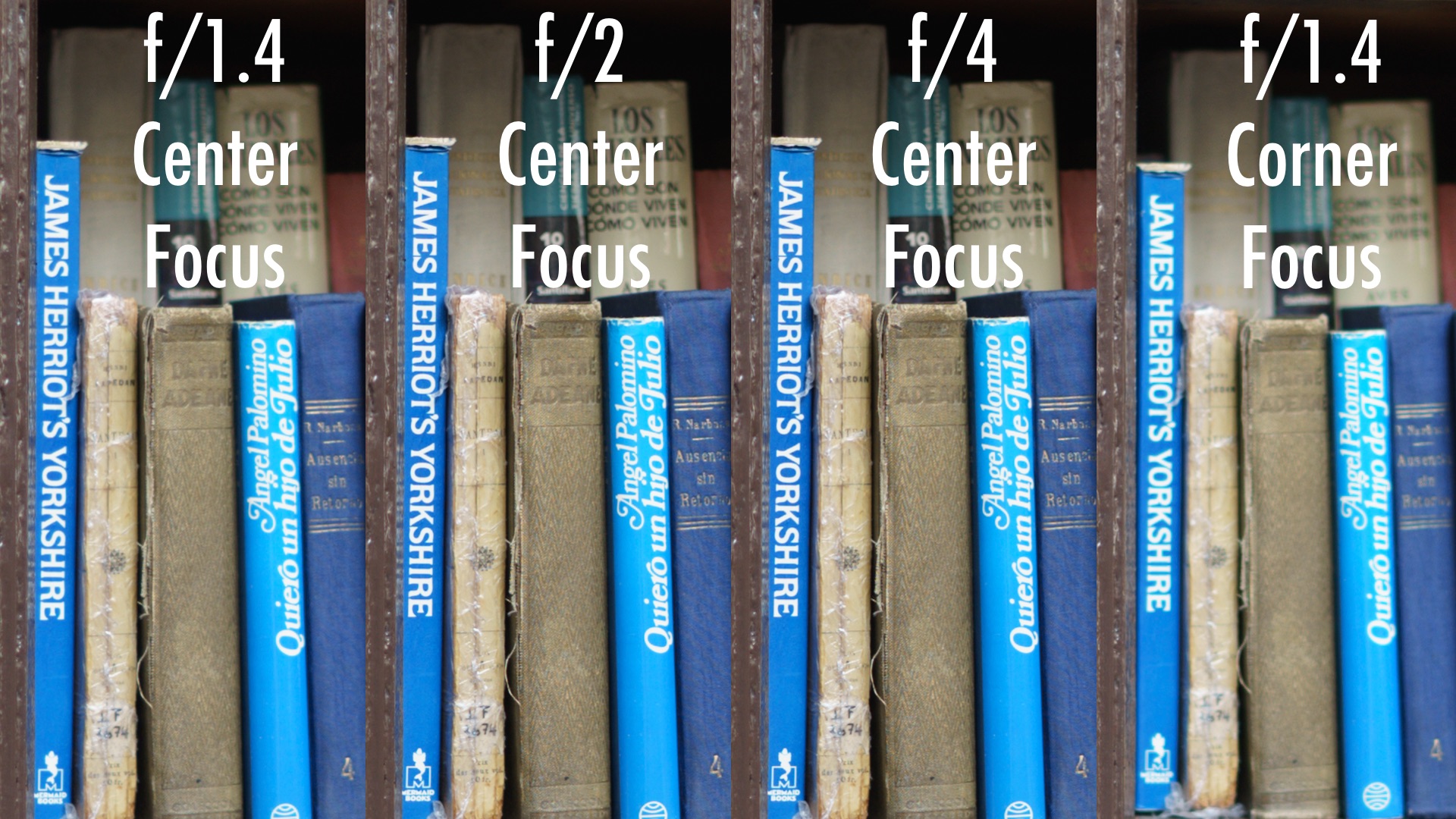

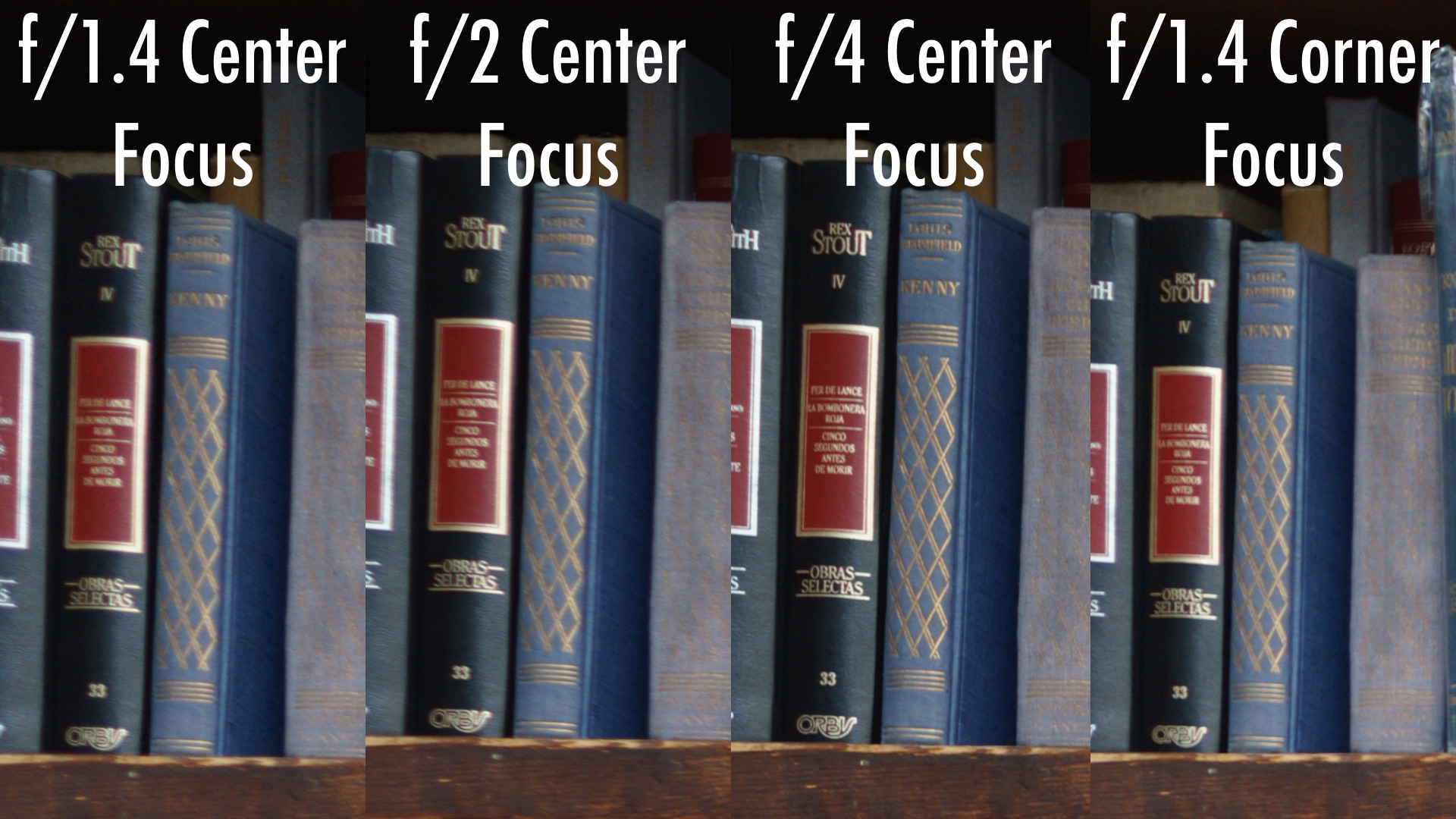

The center is impressively sharp even at f/1.4, and gets razor-like by f/2. Sharpness remains excellent throughout most of the aperture range, and only dips a bit beyond f/11 due to diffraction.

The center is impressively sharp even at f/1.4, and gets razor-like by f/2.

In the corners the situation is a bit more nuanced. The lens is definitely capable of delivering reasonably sharp corners stopped down and even wide open, but depth of field at f/1.4 is so shallow that even the slightest bit of field curvature or subject misalignment will result in out of focus — and therefore slightly soft — corners. By focusing on the corners you can see that the lens is actually sharp, but then you’ll probably get a slightly out of focus center. There’s no way around this, but you should never even see this in real-world usage, unless you spend your days taking pictures of brick walls and then pixel-peeping the results.

The lens can deliver sharp corners stopped down and even wide open, but the shallow depth of field at f/1.4 makes it difficult to get corner-to-corner sharpness in practice dure to field curvature.

Simply put, if you’re not getting sharp images with this lens, you’re doing something wrong.

Bokeh and depth of field

Bokeh is a term that refers to the aesthetic quality of the out of focus areas in an image, not the extent to which they’re out of focus. Some factors that typically affect the bokeh of a lens are the number and grouping of its optical elements, the number of aperture blades it has, and whether those blades are rounded.

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens renders very beautiful and creamy bokeh.

The Sony Zeiss FE 35mm f/1.4 lens has 9 rounded aperture blades which, together with its fast f/1.4 aperture, enable it to create some very beautiful bokeh. Shooting wide open, out of focus areas are extremely soft and non-distracting, even when shooting difficult scenes, and the overall character of the bokeh is fantastic. This is definitely one of the strongest suits of this lens.

Out of focus highlights are rendered circular through most of the frame not only wide open, but also stopped down.

Out of focus highlights are rendered circular through most of the frame not only wide open, but also stopped down. This performance is particularly impressive considering the the lens does not have 11 aperture blades as some of the most recent high-end primes released for the FE system.

Fringes and onion rings in the highlights are kept to a minimum despite the use of aspherical elements, which is also impressive. I don’t know what Sony and Zeiss did to get this lens to deliver such smooth and creamy bokeh, but I’m certinly not complaining.

At the end of the day, bokeh remains a subjective aspect, so it’s best you judge for yourself. Having said that, I do believe you won’t be disappointed by this lens’ performance when it comes to bokeh.

Color rendition and contrast

In the era of Instagram, VSCO film, Filmborn, RNI Flashback, and in-camera film emulation presets, most people’s editing workflows involve applying a preset or filter instead of delivering the native color rendition of the lens in the final image. As a result, native color rendition, contrast, and rendering have become slightly less relevant than they used to be.

That said, there’s a reason many photographers continue to invest in high-end lenses. The rendering of some of these pieces of glass can be extremely unique, and sometimes it can be exactly what the images call for. It’s good to know you can edit the files if you need to, but having a strong starting point is just as important.

As befitting a Zeiss-designed lens, the 35mm f/1.4 delivers impressive color, contrast, and clarity under most lighting conditions. Furthermore, Zeiss’ T* coating also helps reduce glare and preserve contrast even in backlit situations, which is always a nice bonus.

The lens shows the classic Zeiss character: rich and saturated colors, nice contrast and pop.

This lens is awesome for taking all sorts of images from nature to cityscapes, as the colors just pop and the contrast is neither too strong nor too weak. Instead, it’s just right. I love it. If you’re shooting JPEGs, you probably won’t even need to edit your images afterwards.

Shooting RAW, however, is a little different. I often like to apply a medium contrast curve to my images and go from there, but I’ve been surprised by how little editing these images require to look amazing. A truly stellar show here by the Distagon 35mm f/1.4 lens.

Vignetting

Vignetting is light falloff that occurs in the corners of an image, particularly at large apertures.

With such a wide aperture, it’s no surprise the lens suffers quite a bit from vignetting when shooting wide open. This is perfectly normal and, in this case, I actually enjoy the effect it introduces in most of my images. As with most lenses, vignetting cleans up nicely as you stop down the aperture.

Vignetting is moderate to severe at f/1.4, but cleans up nicely as you stop down the aperture.

Having said that, if you use Adobe Lightroom, the built-in lens profile available in the application can automatically correct vignetting at the click of a single button, making it a non-issue in real-world shooting.

Chromatic aberration and fringing

Chromatic aberration (CA) and color fringing refer to the lens’ ability to capture a full range of colors of visible light at the same point. Heavy chromatic aberration typically appears in the form of purple or green fringing around the more contrasty borders of an image.

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens suffers quite a bit from chromatic aberration when shooting wide open, but it goes away pretty quickly as you stop the lens down. By f/2.8 it is all but gone, and even wide open it’s easy to correct in post.

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f1./4 lens shows quite a bit of chromatic aberration and spherochromatism when shooting wide open. Both go away as you stop down and by f/2.8 images are almost perfectly clean.

Spherochromatism is also present, but it’s never too pronounced. Out of focus areas beyond the plane of focus often display green fringes, while areas in front of the plane of focus display magenta fringes. Spherochromatism also goes away as you stop down the lens and can be easily corrected in post.

100% crop showing uncorrected color fringes.

100% crop showing color fringes corrected by the lens profile in Lightroom.

Ghosting and flare

Lens flare may occur when a bright light source is caught in the angle of view of the lens, in such a way that its light rays hit the front element of the lens directly. Those rays may then bounce off other elements or even the sensor itself, producing several artifacts along their path. Lens flare usually presents itself in the form of severe haze and a pronounced loss of contrast across the entire frame.

Modern Zeiss lenses use the famous T* coating, which ostensibly reduces ghosting and flare to a great degree. As such, resistance to flare is quite good with these lenses, although it is still possible to encounter it on occasion.

The 35mm f/1.4 lens has excellent resistance to flare, maintaining very good contrast in most situations. As a habit I tend to always use the lens hoods with my lenses, but I have serious doubts about whether it is actually needed here.

Thanks to the T* coating and the included lens hood, the 35mm f/1.4 lens has excellent resistance to flare.

Distortion

The Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens shows no visible distortion thanks to the automatic lens profile correction. If you shoot JPEG you’ll never see it, and if you edit in Adobe Lightroom you can get rid of it with a single click even when shooting RAW.

For the most part, distortion is well corrected once the lens profile is enabled.

The lens is very well corrected in software, but suffers from slight to moderate barrel distortion natively. You may want to take this into account if your photo editing application of choice doesn’t support lens profiles and/or automatic distortion correction.

Now, there’s a difference between lens distortion — usually in the form of barrel or pincushion distortion — and shift, which causes vertical lines to converge towards or away from the center when the camera is not held perfectly level to the ground. That’s why buildings appear to bend in your pictures: you’re pointing the camera up to get them to fit into the frame.

All lenses, including the Zeiss 35mm f/1.4, suffer from shift distortion, but it is more apparent with wide angle lenses because that’s what people normally use to take pictures of buildings with lots of straight vertical lines. This effect is unavoidable and entirely caused by the laws of physics. When the subject plane (the building) is not parallel to the image plane (the sensor), vertical lines converge because they are projected onto a non-parallel surface.

Shift distortion causes vertical lines to converge towards the center when aiming the camera up.

Shift can still be corrected in post-production at the cost of some resolution and image area, but it isn’t a fault of the lens. If you don’t want to see converging vertical lines in your images, your best option is to ensure your camera is level, or to use a tilt-shift lens, which can shift its imaging plane relative to the sensor to compensate for this effect.

Shift can be corrected in post-production at the cost of some resolution and image area. An alternative is to use a tilt-shift lens instead.

Finally, the 35mm field of view is moderate enough that perspective distortion isn’t usually a problem. Just make sure you’re not placing the camera super close to your subject and you should be fine.

The 35mm field of view isn’t wide enough so as to introduce severe perspective distortion.

Real world usage and image samples

Shooting with a fast 35mm prime is a very special process, and one I enjoy immensely. There’s just something unique about the way the world looks when seen through the 35mm field of view, especially at f/1.4. Subjects have a way of looking dreamy while still being recognizably themselves, and mundane objects and places somehow look more interesting.

I’ve long craved that look for my images, which is why the Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens had been on my list of future purchases ever since it was announced. However, up until a few months ago I hadn’t been able to justify spending so much on a lens. Luckily, I was finally able to take the plunge after saving up for a while. To be honest, I have never looked back.

I will admit to being concerned about the size and weight of the lens, though. I also own the Sony FE 70-200mm F4 lens, which is bigger and heavier than this one, and I dread the thought of carrying it with me for an entire day just in case a photo opportunity presents itself. Funnily enough, that’s never happened to me with the Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens.

Do you know how people often say the images are worth carrying the extra weight? At some level I thought I understood what they meant, but I didn’t really. I surely get it now.

Ideally, I’d still like to own a smaller and lighter lens for the most casual of photo walks, but if I’m going to be shooting anything that’s even remotely important to me, this lens is definitely going to be in my bag, and probably attached to my camera. It’s that good.

Although its size can deter from wanting to carry the lens everywhere, if I want to shoot a keeper, this is the lens I’m going to shoot it with.

I don’t really know how else to put it into words. You’ve already read all about the performance and image quality, so I won’t bore you again with more of the same. Suffice it to say: yes, image quality is spectacular, but that’s not why you buy this lens over a cheaper, slower prime. You buy it for the unique way it lets you look at the world, and the people in it. You buy it because there’s nothing else out there that can produce that magic.

In the few months I’ve owned it, I’ve mostly used this lens to shoot landscapes, often in my beloved city of Madrid. In that time, I’ve been repeatedly amazed by how this lens has allowed me to discover an entirely new side to the city — my city — in a way I never even thought possible. I can’t tell you how much I’m enjoying walking along the same old streets and looking at the same old buildings as if it’s the first time I’m seeing them. Again, it’s not a feeling I can explain or possibly do justice with mere words, so hopefully you’ll be able to get a glimpse of what I mean by looking at the images in this review.

In the few months I’ve owned it, I’ve mostly used this lens to shoot landscapes, often in my beloved city of Madrid.

That’s been the fun and rewarding part about using this lens so far.

Now, for the challenges.

Being a rather big lens, the Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens is not exactly what you would call discreet. It looks big and bulky, and it will make you stand out from the usual crowd of tourists and casual photographers like a sore thumb. If you want to use it for street photography, you may want to take that into account.

Now, I’m not a shy photographer when I’m shooting on the streets. I have no problem asking people for a picture and generally getting up close to my subjects to get the shot. Most times people don’t even notice, and sometimes they do. I’m ok with that and I’ve never had any problems in the past.

However, during one of my first photo walks with the Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 lens, I did have a rather unpleasant encounter with an inebriated man who thought I had taken his picture. I hadn’t, so I just showed him the last few images and he quickly eased up. Luckily I’m usually good at defusing those situations before they escalate, but it was a very tense moment and it did leave me a bit shaken for a while.

Like they say, the best way to get over a bad riding experience is to get back on the horse right away, so that’s what I did. I’m happy to say I haven’t had any more unpleasant encounters since then, so maybe we can simply chalk it up to coincidence and/or bad luck. I may have subconsciously been a bit more cautious and aware of my surroundings since then, too. At the end of the day, I do believe it’s OK to use this lens for street photography, and I certainly plan to continue doing so. Which is actually a nice segue into the last point I want to make.

One area I haven’t explored nearly as much as I’d like with this lens is environmental portraiture. Environmental portraiture is definitely one of the strong suits of 35mm fast primes, so I’m eager to put this one through its paces and see what happens. I’m curious to see how it renders faces, bodies, light, and all of them combined. It’s going to be an awesome creative challenge for me over the next few months.

There are no guarantees in photography, but if the lens does even half as well as it’s done for everything else so far, it’s going to be an enjoyable journey.

I can’t wait to get started.

Room for improvement

The Sony Zeiss FE 35mm f/1.4 is an impressive performer, but no lens is perfect. Here are some areas that could be improved upon:

11 aperture blades: It’s hard to objectively tell whether putting two more blades in this lens would result in better image quality, but the fact remains that Sony has set the standard for their top-shelf FE lenses at 11 blades, and this is the only one still lagging behind with 9.

Tougher weather-sealing: There’s some controversy going on with Sony lenses when it comes to weather-sealing. Sony only advertises them as being “dust and moisture resistant”, while other companies flat out state their lenses are weather-sealed. This has led many to assume that Sony’s technology is somehow less effective. For what it’s worth, I’ve used all my Sony FE lenses in the rain, and I’ve never had any problems. Of course, there are no guarantees, so do so only at your own risk. In any case, Sony should be more straightforward about this — either come out and say the lenses are actually weather-sealed, or make them so.

Better quality control: My slightly loose aperture de-clicking switch is something that should not happen in a $1,600 lens. Better quality control in the manufacturing chain is a must.

A more affordable price: Yes, this lens is good, but it’s also twice the price of the also-superb Sigma 35mm f/1.4 Art prime. For now, Sigma doesn’t make native FE lenses. But no matter how you look at it, a price of $1,600 for the Sony Zeiss lens is not sustainable in the long run.

That’s pretty much it. As you can see, aside from price, the rest of these are fairly minor issues. Whichever way you slice it, the Sony Zeiss 35mm f/1.4 is an absolutely stunning lens.

A loose de-clicking switch is something that should not happen in a $1,600 lens.

Alternatives

I’ll make it simple for you: if you want native performance, size doesn’t bother you, and you can afford the price tag of this lens, just buy it. It is the best option available for the FE system all things considered, and you’ll never regret buying it.

However, if any of those factors is a deal breaker for you, here are some alternatives you can consider:

The Sony Zeiss FE 35mm f/2.8 lens: This tiny gem of a lens packs impressive image quality into a tiny, weather-sealed and affordable body. If you don’t need the extra two stops of speed, it is a no-brainer. Also, if your budget doesn’t quite allow for the more extravagant Distagon lens, this is a very good compromise that will still produce superb images with the same Zeiss color, contrast and pop.

The Zeiss Loxia 35mm f/2 lens: A very different animal, but also smaller and also a great performer. While some reviewers have criticized this lens for having a rather nervous bokeh, the 35mm Loxia is still wonderful in terms of color rendition, contrast, sharpness, and overall image quality. It’s a lot smaller than the Distagon, but surprisingly hefty due to its all-metal construction. At f/2, it’s still fast enough for most needs. Of course, the biggest difference with the Loxia is the fact it’s a fully manual focus lens. If that’s your cup of tea, the Loxia is an awesome lens.

Those are the two other native 35mm prime lenses in the FE system, and they’re both worthy purchases if your needs are different from what the 35mm Distagon brings to the table. Now, I generally advise against adapting lenses from other systems, but in this case I’m going to make an exception — the Sigma 35mm f/1.4 Art is just too good to ignore. If you couple that lens with either Sigma’s own MC-11 adapter or the Metabones Mark IV, you’ll be getting very similar image quality at a substantially lower cost. You won’t get the same AF performance, but it won’t be terrible either, so the choice is up to you. I still recommend going with the native lens if your budget allows for it — as I did myself — but I realize sometimes that’s not an option. If that’s your case, fear not: the Sigma is a truly wonderful piece of glass.

Final words

Remember what I said in the beginning about life being full of hard choices?

Well, that may be true. But as it turns out, this isn’t one of them. The Sony Zeiss Distagon T* FE 35mm f/1.4 ZA is a truly phenomenal piece of glass and easily the best lens I’ve ever shot with, period. If you’re in the market for a fast 35mm prime, you needn’t look any further.

When it comes to choices, it really doesn’t get any easier than this.