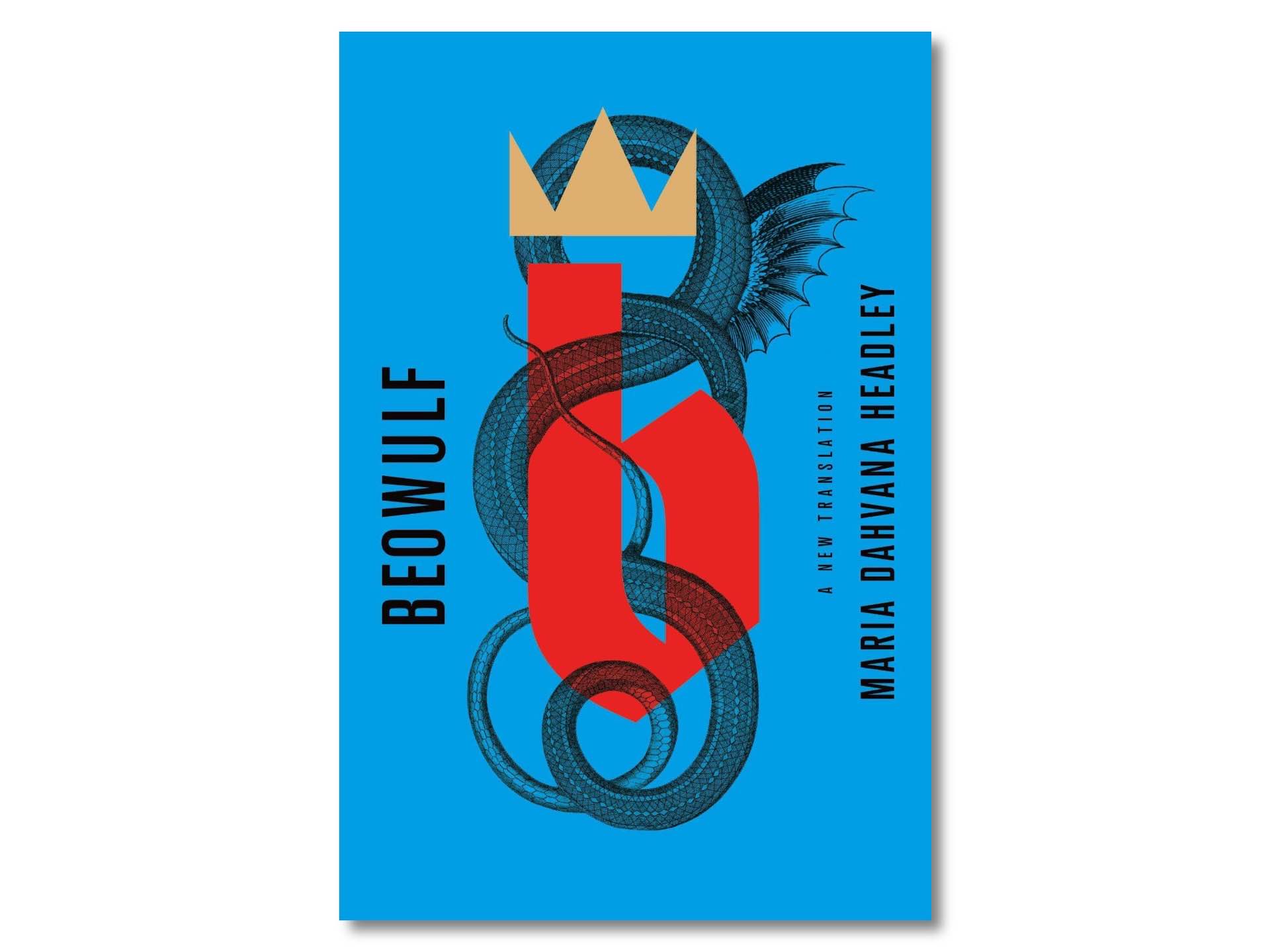

‘Beowulf: A New Translation’ by Maria Dahvana Headley

Beowulf begins with the Old English word “Hwæt!” which is a tricky one. It has often been translated as “Listen!” or the somewhat musty “Lo!”

Seamus Heaney used “So!”—a nice twist.

Now, Maria Dahvana Headley opens her new translation…

with…

“Bro!” 😎

Robin Sloan (@robinsloan)

Released just the other day, Maria Dahvana Headley’s Beowulf: A New Translation is the latest entry in the ongoing trend of feminist retellings of ancient tales, similarly breathing new life into an old classic.

And I don’t mean that she’s done like so many before her and merely tried to clarify the Old English text of this epic poem for today’s audience — she’s thoroughly modernized it. It’s almost Hamilton-like how characters throw around modern swears and slang (including the likes of “hashtag: blessed”, “swole”, and “stan”), though it does retain some archaic kennings in the mix.

From what I just described, you might think the story has been dumbed down in some way, but no — the poetry is as evocative as ever; the recountings of battle are as exhilirating and engrossing as they ought to be, like hearing them firsthand in a friendly tavern; there is so much heart in this tale, and it’s more accessible than ever.

In the book’s extensive introduction, Headley writes:

I came to this project as a novelist, interested specifically in rendering the story continuously and clearly, while also creating a text that feels as bloody and juicy as I think it ought to feel. Despite its reputation to generations of unwilling students, forced as freshmen into arduous translations, Beowulf is a living text in a dead language, the kind of thing meant to be shouted over a crowd of drunk celebrants. Even though it was probably written down in the quiet confines of a scriptorium, Beowulf is not a quiet poem. It’s a dazzling, furious, funny, vicious, desperate, hungry, beautiful, mutinous, maudlin, supernatural, rapturous shout.

In contrast to the methods of some previous translators, I let the poem’s story lead me to its style. The lines in this translation were structured for speaking, and for speaking in contemporary rhythms. The poets I’m most interested in are those who use language as instrument, inventing words and creating forms as necessary, in the service of voice. I come from the land of cowboy poets, and while theirs is not the style I used for this translation, I did spend a lot of time imagining the narrator as an old-timer at the end of the bar, periodically pounding his glass and demanding another. I saw it with my own eyes.

If you were forced to read this story in high school and dread the very idea of revisiting it, put those fears to rest because this is easily one of the most fun and entertaining reads of 2020. I mean it.

Get the book in these formats:

- Kindle ($10)

- Apple Books ($10)

- Paperback ($14)

- Audible audiobook ($21)

- Audio CD ($29)